What types of ships come through the Port of Vancouver?

The Port of Vancouver handles the most diversified range of cargo of any port in North America so there is a range of ships you can see in our waters at any given time. They may be alongside one of the port’s terminals in Burrard Inlet, Roberts Bank or the Fraser River, in transit, or anchored at one of 20 anchorages in English Bay, eight in the inner harbour, or five beyond the Second Narrows and into Indian Arm. Ships will anchor while they wait their turn to load cargo at a terminal in the harbour.

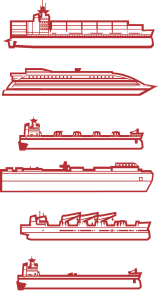

Here are the kinds of ships you can expect to see transiting the port:

As for the sounds of the port, terminal operations and activities are industrial by nature and occur on a 24/7 basis, and many sounds, such as sirens and vessel horns, are for safety reasons. For example, international regulations require vessels in sight of one another to alert other vessels in advance of maneuvering. This can be done with either sound and light signals or a combination of the two.

- One short horn blast or light flash means “I am altering my course to starboard”

- Two short horn blasts or light flashes means “I am altering my course to port”

- Three short horn blasts or light flashes means “I am operating astern propulsion”

Vessels are also required to signal their position to others vessels in periods of reduced visibility, which can include fog, snow or rain.

When out on the water you may also see ships releasing large quantities of water. Ships wash their anchors with seawater while they are being hoisted to clean mud and debris from the anchor and its chain. This helps avoid moving contaminants from one harbour to another and protects the crew from flying residue. Anchor shackles are marked with different colour paint so the crew can tell how much chain is out.

This is not to be confused with the release of ballast water. People often mistake the reason for over-side discharges. A deep-sea vessel is almost continuously suctioning seawater for various onboard systems and to ensure the ship is weighted properly in relation to the amount of cargo on board. For example, aside from cleaning, seawater is also used to cool a vessel’s main engine and generators. Once the water flows through the pipes and cools the equipment, it is discharged.

The Vancouver Fraser Port Authority was the first in North America to prohibit in-port ballast water exchange without prior mid-ocean exchange, to prevent the transfer of invasive species. Exchanging ballast water 200 nautical miles from shore in waters that are at least 2,000 metres deep currently provides the best available option to reduce the risk of introduction and transfer of alien species. This practice became the basis of government requirements now enforced by Transport Canada and adopted by many other countries.

For more information on sharing the water with trade vessels, visit portvancouver.com/safeboating.